Summit to talk about

Last Tuesday’s speaker

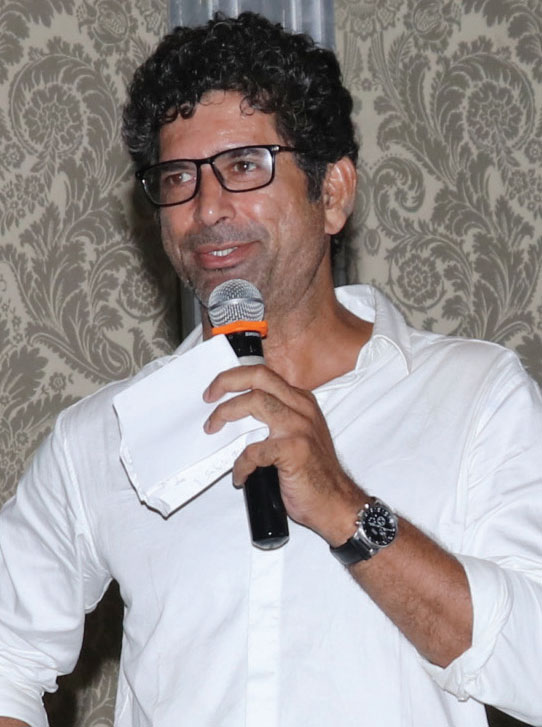

Advait Dikshit talks about the road to summiting Mount

Everest and his challenges with diabetes

By adventure projects, Advait means assignments that take him out of his comfort zone. “These are projects that allow me to test systems, processes, frameworks and theories that I have learnt and heard from people. That way, I can validate them for myself and internalise them. Whatever the success and failure I have in my projects, I bring them

back to my professional work; that is how I complete this virtual cycle – that is my trip and life.”

Advait’s talk was divided into four sections: adversity, adventure, demonstration and contribution. His topic: ‘Sugar to snow: backpacking from adversity to adventure’.

One of the expeditions that Advait shared with Rotarians was of cycling from Kanyakumari to Kashmir, all by himself and with luggage that weighed 30 kg.

The real story, however, starts upon his return from the expedition, when he find out he had diabetes. “I actually howled at a rock cliff and then blamed my parents. Both my maternal as well as paternal grandmothers died of diabetic trauma. So, yes, that is my lineage!”

“After spending a month in semi-depression, I resolved I could not go on like that any longer. My life could not be about continual monitoring of blood sugar, medication and all the stress that goes with that. Life gets constricted!”

“I didn’t want that so I decided to turn this adversity into adventure! How about becoming healthier? Not to survive diabetes or control it but to actually go to the next level in terms of performance. I shared this with all my friends on Facebook and once you do something like that, you are trapped. There is no going back.”

“I said to myself, how about summiting Everest? I’m 55-years-old, diabetic, without any medication, and I want to climb to 9000 metre and summit the Everest. A woman I met on my cycling expedition inspired me to do this. So, I called her up and thanked her.”

One of the earliest challenges towards preparation was fasting. He decided to go three days on water. “Day 1 went by. Somehow, I stayed away from food by watching TV. By the afternoon of the second day, I was going crazy. I landed up at Starbucks. There is something destructive in me, I always end up where I shouldn’t be. So I was at Starbucks with a blueberry cheesecake in front of me. All I wanted was that cheesecake. Then there were two voices in my head, one of which was an admonishing parental voice saying, ‘What about your declaration? What about going to the Everest? Two years of training and this is just the first step.’ Then there was another voice: ‘Don’t be so hard on yourself, it’s okay!’”

“Finally, I told myself: ‘Advait, it is okay to have that cheesecake. Relax. The battle is over. You can have the cheesecake. Suddenly I felt the energy coming back, the focus coming back. I was not even looking at the cheesecake anymore because now I could have it, right? The space that got generated in my head from the absence of the conflict allowed a creative thought to come in. And it said, ‘Advait, you can have the cheesecake but you know what, why don’t we go on YouTube and see videos of some other people who have done a three-day fast.’ I thought that was a good

idea.”

He did not find any videos of people who had done three day fasts but stumbled upon several of people who had done 20-day fasts and more. He read articles on people who had done 362-day fasts on just water. “I found myself looking at the people who had done the 20-day fasts and saying to myself, ‘If this moron can do it, so can I.’ I kept listening to them and turning them into my mentors. I ended up fasting for 20 days on just water. I broke it at the Yacht Club on the 26th of December, out of boredom. I had two oranges.”

This experience crystallised certain principles for him. These were principles he had learned from Alcoholics Anonymous, being an addict for 14 years. They were: 1. Be a contrarian: Find the different out of the ordinary. He explains, “When I was struggling with my addiction, if I had gone to my relatives or doctors, they would have said: ‘Control, Advait! Get control of yourself.’ But the control thing didn’t work well for me and I landed up in Alcoholic Anonymous. They told me the exact opposite. They said, ‘Give up control.’ In fact, the first step of Alcoholics Anonymous is to admit that we are powerless over our addiction and our life has become unmanageable. It seems completely counterintuitive to go to get power or control and to be told that what you had to do was give it up. Even merely desiring to believe it incites fear in me. About 99 percent of contrarian thoughts are contrarian because they don’t work but if you can find the one that does, then that’s the breakthrough. So, keep searching for alternative points of view which are criticised, denounced or laughed off. In that haystack, you may find the one gem that will take you to the next level.”

2. Stick to winners: “If I identify one contrarian thought, who is the champion of that thought? That person is the winner. Stick to that person, hang around with that person. Identify role models and follow them. Keep your brain aside for a while and follow that person until you get creative.”

3. Hang around with peers: “These are your equals, your community. When I was struggling with the cheesecake, who was with me in the videos? My community! I hung around with these friends and not with the Starbucks friends, and so I could fast for 26 days.”

4. Contribution: “Can I actively seek out people who are few steps behind me? Can I teach them my success, failure and my struggle?”

Coming back to Everest, Advait was a novice when he began. He says, “I had never trekked, cycled, stayed away from lunch for more than two hours. So, I began with a decision to go stay amidst mountains. I went to Ladakh. Then I failed and realised I needed to have a worldclass coach with the same principles as me.”

“I found Steve House, an elite mountaineer. I was very excited and he heard me patiently for 30 minutes. Then, he said, ‘There is no glory on Everest, Advait! If you want to find glory, find a cure for cancer or feed the hungry! That’s where the glory is.’ Later, in an email, he wrote: ‘The day you learn to love the process and forget all about actual scaling, that’s the day you will be a mountaineer.’ I am beginning to love the process. To learn about oneself, to learn about the environment, that’s the game. More than process, it’s also about contribution. Maybe I have not summed this last part well, but the process has begun!”

While in Ladakh, he read a line in a Buddhist philosophy book: ‘When you die, you will not be asked why you were not a Buddha, you will be asked, ‘Why were you not Advait?’

“Suppose something goes wrong at the Everest Summit, if I am lying down and I have no energy to get up and go down. I have to ask myself, ‘Were you Advait?’ The answer will be, ‘No’. There will be a hint of regret. So what can I do now so that the chances of that regret reduce by May 2020. My answer is that is where sugar to snow is. This journey started with me discovering a problem that I have, sugar, which I have to survive. I discarded this to actually summiting the Everest to demonstrate that my performance can actually go to a level better than before I had diabetes. That journey has to be shared with people. It is in the contribution of sharing the journey with people and not in summiting the Everest that my fulfilment will be found. Most of the time I don’t believe in this, and that’s the breakthrough.”

“I want to reach out to people above 35 and 45. My idea is that India is going to be the diabetic capital of the world, it needs to hear this message. Lifestyle changes can reverse this and, even better, please don’t change your lifestyle just because you got money. That is a bigger message, that’s the contribution I want to make. I want to demonstrate that one can thrive with any kind of lifestyle disease.”

“That’s my project, that’s what I am up to. Before I end, this is what I’d like to tell Steve, ‘ I am a little closer to understanding what you said two years ago. It is not about the Everest, there is no glory there. If possible, contribute. That’s where the joy is. If it ever happens that you are up there and you can’t return, there is one thing you won’t have, ‘Regret!’ Then, I can die answering ‘Were you Advait?’ with: ‘Yeah!’”

- This photo of a serpentine queue on Hillary Step, a well-known choke-point close to the summit of Mount Everest, is going viral. It shows a long line of trekkers walking along a precarious cliff waiting to fulfil their dream. The route was clogged as 250-300 people marched in a single-file, reportedly taking up to three hours to summit. The photo has triggered a stormy debate about over-crowding atop the mountain.