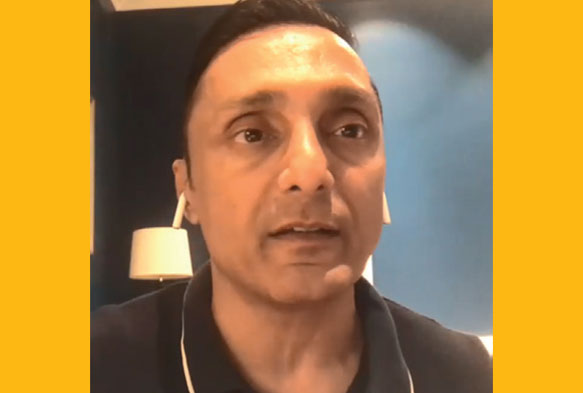

‘Failure brings out the best in you’: Guest speaker Rahul Bose talks about life lessons

WHEN PEOPLE SPEAK ABOUT LIFE LESSONS, IT IS USUALLY ABOUT THEIR GREATEST TRIUMPHS, THEIR GREATEST SUCCESSES, HOW THEY HAVE GOT WHAT THEY GOT. I THOUGHT ALL OF YOU DESERVE BETTER. SOMETIMES, FAILURE AND ITS DARKENING SHADOW BRING OUT THE BEST IN YOU – A QUALITY THAT SUCCESS COULD NOT HAVE PROBABLY EXTRACTED.

Let me share three of the potential failures of my life that ended on better notes but did not spare me humiliation, public ridicule, self- doubt and, also, doubt amongst the people around me. Telling you the stories will do justice to all of you in terms of maybe listening to something off the expected kind of talk.

I inhabit three worlds: the worlds of cinema, rugby and non-profit. I have acted in over 35 films and directed two. I have played every single International Rugby tournament that India has participated in from 1998 to 2009. 1998 was the year when India was officially recognised as rugby-playing nation after which I was on the board of Indian Rugby. I then left that to raise money and work on raising the profile of the game unfettered. The world of nonprofit came later in my life. I established the foundation in 2006 and it remains, to the best to our knowledge, the only NGO to do the work it is doing.

The other NGO I run is called HEAL which is the prime emotional driver of my life to create a world where children don’t have to face pain and, of course, that is unrealistic but I aim to prevent the pain, trauma and lifelong scar of child sexual abuse. I am going to share stories from each of these lives and these are the toughest stories that I have to share.

Starting with cinema: I had been acting on the stage for five to six years, but I was just starting my career as a film actor. The difference between the two was that in films, there is no appreciation. You act for days, weeks and imagining the applause in your head. If you are lucky, fame awaits you after the film’s release. It is exponentially higher than the fame that any other career can give you.

The second and more important difference as an actor is that you do not know if it is working. On a bad day on stage, when you don’t get the kind of laugh that a line was supposed to get, you realise that you have to up your game. On the other hand when you are pushing so hard that the audience almost recoils, you take a deep breath and allow yourself to let it flow more naturally. In cinema, there is no feedback.

Secondly, it is so disjointed, because on day one you are shooting Scene 83 where you are at your father’s funeral, on day two you are shooting a flash back where you are eating ice-cream with your father at Chowpatty. So, to arc the character emotionally, chronologically, is also something that requires a lot of vigilance on the outside. So, who do you depend on? You already depend on the media and obviously if there is a co-actor who you can turn to, or maybe a crew member candid enough to tell you.

Otherwise, you are pretty much at the mercy of one or two people. In my case, there was excellent guidance on what was needed from me on screen but there was also lack of affirmation, lack of open encouragement. Actors only need one thing: to be told that they are the best, to be told that what they are doing is fantastic. It works magnificently even if it is a lie, and even if the actor knows it is a lie, because then we will walk with you till the end of the world.

I never got the kind of feedback on the day of performance that I could hold on to in terms of creating a sort of emotional arc. We were filming in undivided Andhra Pradesh and it was tough shooting in a village where, whether you ordered a dosa, idli or wada, you would always get a bowl of sand. To make life easier, the sand would be mixed in the batter. So it was tough nutritionally, I think I must have ingested enough silicon to make a super model jealous. And the place I was trying to get this at, the crew had already tried their best as it was the best village. However, on one side of it was the busiest petrol pump in the world with cars and lorries and the stench of urine rising from the bathroom in the petrol pump. All of that wafted in helpfully through my window because the hotel was air-conditioned. On the other side seemed to be the most popular temple in the world where temple bells would ring early in the morning.

So, while the gas station quieted down at 3.30 am, the temple bells started at approximately 4 am. Technically, I had about 29 minutes of silent sleep. To shorten a long story, it was a challenge. Every day when I went back to my room, I would ask myself, ‘had I done okay? Could I have done better? Was it right?’ I remember thinking to myself, ‘You just do what feels right’. Instinct coupled with experience are the best assistance to take you through situations that you haven’t been under.

I pulled down all my experience as a theatre actor, all my instincts to tell whether I was hitting the right thing or not and I powered through. Fast forward one year to the middle of the ’90s, and at the Grand Slam of world-famous film festivals: Toronto, Berlin and Cannes. This film got selected for the Toronto International Film Festival which is a big deal.

I was invited, and I was like I have not even seen the film and I am going to Toronto. They said, ‘Don’t worry, you will see it there.’ So, there I was, sitting in a theatre with 600 other people; I hadn’t eaten all day, butterflies in my stomach, sweating in an air-conditioned auditorium, watching myself on the screen for the first time. I can promise you that I was not watching so much the film as I was watching myself. And as scene by scene go by, I was grading myself. When the film was over, I was drenched in sweat and I honestly said to myself, ‘I think it is okay’.

There were 599 people in the packed hall who did not know who I was, who might have never been to India, or experienced the culture. The director was called on stage for the Q&A and he, in turn, called me. I came up on the stage and 600 people just stood up and began to clap. We have all seen standing ovations when someone is getting a lifetime achievement award. I was a stranger and they were standing and clapping. This lesson solidified and hit home that the best chance you have in your life is that when you don’t know whether it is right or not, go with your instincts. What is the worst that could have happened? I could have failed. I would have come on stage and there would have been stone-cold silence. But at least I would know that I had pulled the best inside me from my brain and my heart and that I would be able to walk away head held high.

The second story is that from my non-profit work. I started the foundation in 2006 but my first real engagement in non-profit was in 2002 when I began to work on gender discrimination and gender justice. That still remains a pre-occupation. In 2004, the tsunami hit Indonesia, parts of the southern India, Sri Lanka and Andaman Nicobar Islands. I was sitting in front of the TV on December 26th, 2004 watching, in horror, the kind of devastation the tsunami had caused and specifically watching all the footage from the Andaman Nicobar Islands.

Firstly, little was coming out of there and secondly, who was helping them? By now, there were hundreds of NGOs helping Nagapattinam, Chennai, Coonoor, Sri Lanka and Indonesia. For two and a half days, I kept watching and then somewhere a bell rang that maybe I should go to Andaman Nicobar and see what we can do.

I didn’t have an NGO of my own, but I had wonderful friends who ran NGOs across the city, I called them and made a plea. They called other NGOs, we called ourselves the Solidarity Network and they said ‘Go to the Andamans. Be our eyes and ears, tell us what is needed and we will collect funds and send targeted relief.’ That was perfect because no one needed blankets in 42 degrees heat. I would get there and see what was needed. At that time, I am not ashamed to admit this, but Andaman Nicobar was not at the centre of our consciousness; I didn’t know that it took another two hours to fly from Chennai, or that the northern tip of the archipelago is closer to Indonesia than to India. I didn’t know that there are 576 islands in the archipelago out of which now 37 are inhabited. I didn’t know that the population was of Colaba – five and a half lakhs.

In the islands, my gut feeling was right. While there were 300 NGOs working in southern India, there were just five in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. At this time, there had been a lot of publicity about a movie actor who had gone there with pledges to resurrect the fortunes of many villages in India. He had made power-point presentations to the collector, there were photographs of him, sweating madly holding packets of wheat and handing it to the poor villagers and the public. After this, he vanished and never looked back again.

So when I went there and met an official in the relief division at the islands, he said, “Oh, Mr. Bose I heard you are coming. So, you have come to gain cheap publicity!”

I said, “No, actually I haven’t told anyone that I am coming here, I didn’t know myself till yesterday. I am here representing 20 NGOs, I am partner of Solidarity Network, I am here to see and report and then we will send relief and rehabilitation in due time.”

He said, “No, no! you don’t have to use this for your publicity. If you are really serious about relief and rehabilitation, you don’t have to go anywhere. You sit in the office and write down in triplicate what relief you are going to provide and when. Give me a copy, you keep a copy and we will file the copy in the office so we can keep track whether you have kept your word or not.”

I said, “How will we buy materials if we don’t know what is needed?”

He said, “You don’t need to know it, I will tell you. Write down.”

He made me write down what believed was needed in the 36 islands.

I asked, “Have you been to these islands?”

He said, “I don’t need to go, I have all the information.” At that time, I decided to leave.

I had come to the islands with Amitav Ghosh, a dear friend of mine and a fine writer in the English language. When I went back to hotel and told Amitav what had happened, he said, “Look Rahul, if what you want to do is eliminate pain in India, you can go to any part of India. Why do you want to wait for the tsunami? Go anywhere. Why do you want to face this kind of humiliation?”

I said, “No, I will stay and fight this out.”

Then the islands were opened up for journalists and people to visit, but I was taken off the list of people allowed to visit. Another official put me back on the list. I was on the plane taking off to visit the affected areas and this official sent someone into the plane to pick me up and to lead me off the plane. Then I decided that when you are faced with absolute intransigence at a humane level from someone who controls your life, then you have to go over that person’s head. If somebody is doing something that is clearly anti-human then you should break the rules, you are justified to break the rules.

Rules are made to preserve humanity, compassion, love. So, I went to this boss’s boss’s boss’s boss in a huge office in Delhi and said one thing, “This gentleman is anti-human”. I ended up spending 30 months in the Andamans, I made 30 trips in 30 months. We organised two container shipping loads of relief from digging tools to pesticides to milk powder to things specifically needed to prevent diseases. I began my foundation in 2006. We selected six kids from the Andamans to be educated, nurtured and raised outside of the islands in the best schools and colleges of excellence. They are all 25 years old now, they are all going to go back at 30 to change the developmental fortunes of the Andamans. Right now, just a small example, the first architect in design graduate in the history of the Andamans is a tribal girl who is now working in one of the top design outlets of the country and will soon be going back to Nicobar to start her own design school for children. The lesson I learnt was that when you are faced with people who are anti-human, things are meant to be done and laws are needed to be broken to uphold the larger reason in society.

My last story is the toughest, from the world of International Rugby. I played from 10 years from 1998 to 2008, the Commonwealth Games were happening in 2010 and I didn’t want to be 43 and occupy the space and oxygen that a younger player can or benefit from the influx of funds during the Commonwealth Games, play for India, have excellent coaching. I decided to call for my retirement so that the new blood had 18 months for the team and to be a part of it.

There was a triangle taking place between Philippines, India and Malaysia and I announced my retirement. The Rugby Union, the test match of Rugby Union vs the ODI T20 version is played by 15 people in each team. So, 30 people on the field and there are substitutes ranging from 16-22. Unlike in other sports, in Rugby everyone plays because you are so exhausted. The substitutes come on and you invariably get 25-30 minutes of solid Rugby from your substitutes and if your subs are weak, you are going to lose a game.

By 2008 I am not good enough to make the top 15 for India but I am good enough to be the sub and I am 19. So, I am waiting on the bench and we play the first Test match and now I am playing my final Test match of India against the Philippines and I know that I will come in the second half, I am aware that I am not starting and that is fine. It is very well deserved. So, I am waiting, we are winning, in the second half in minute 47, the coach says number 16 out, so, he starts warming up, then he says number 17 get on, all of us are still warming up. In minute 63 he says, 18 you are on, 19 goes on in minute 67, 20 goes in minute 70, 21 in 72 and we are warming up and we are winning and coasting. 72-72-74-75-76-77-78-79-80-extra time – three minutes – 81-82-83. And out of 44 players playing International Rugby for their country that day, 43 played and one didn’t.

Boys came up the from the field, rejoicing, realised something. They asked why didn’t I come on, on the team bus, and for celebrations. And I was one dark hole of despair sitting, I wished I could die, I wished I was invisible. I didn’t want to ruin their moment, these are my brothers, I have shared blood with them. We went to the room and my roommate considerately left the room. I locked the room, had a shower and left. I came down and asked the concierge, ‘where is the nearest bar?’ He said, ‘across the road’. I went there and I started drinking from 6 in the evening to about 1 in the morning and I am stone cold. I am drinking continuously.

At 1.30 the phone starts buzzing with messages, ‘Bose, where are you, we have just finished dinner, we are going to hang out at the club, the coach is also here’. The coach who didn’t let me play is also there. This is the last time we can ever be together, so I go and the first person I head to is the coach and I ask only one question: ‘why?’

He gives me the most violent answer I have ever got in life. He says nothing, he just keeps looking. And that is the time I decided that I will not retire, I cannot go. So I come back to Bombay, 41 years of age, I hire my own sprint coach, my own conditioning coach, my own fitness coach and I start training.

The boys see me and they say he is going to make a fool of himself, next year he is going to be 42, why is he doing this? But I can’t not! Next year, a camp is called before the next triangular in Singapore for the 60 probables, I am in the camp, there is a fitness camp conducted to cut the 60 to 30 after a week, I make the 30, I am 8th on the fitness roster. That 30 is cut down to 26, to 22 who will play for India, I make the 22. And I can only see that I didn’t finish my career playing in the second half for India. I played in the first half and the lesson from this: every one of you, including me, has not got the credit for something he or she has done, every one of us has dread of public humiliation. When that happens, you should become so good that you shame them – that is how strongly focussed you have to be.

ROTARIANS ASK

What did you do to overcome the rejections and reverse the table?

You deserve better and you need to feel better about yourself, the sense of trying to rectify what you see, the perception around you, we are very human and we relay a lot on the affirmation of people we value who we consider our cerebral and emotional peers. So that is also a big drive. I was always taught, in Rugby they say, to leave your body on the field at the end. And including this talk today, I don’t hold back, I’ll do the best in the time given to give you something that you don’t have.

Which of these roles you enjoyed the much?

They feed different parts of my body. My NGO feeds my heart, Rugby feeds the sportsman soul and acting of course suffices every single role of my body. It is difficult to prioritize but 20 years ago it would have been actor, today it is more important for me to feel that I have been a peaceful and compassionate human being. You might not like my last role but this is something you cannot take away from me. It is ethical to be ideologically not discriminatory, to be inclusive and loving. There will always be a more loving, empathetic and warm way out of things, to talk your way out of the things.

How are you keeping up now with the gyms closed?

It has been in phases. When the lockdown happened and we were still allowed on the roads for a few days, I ran all over the city. Then the roads were shut but you could go to some of the parks and grounds. Then, with lockdown and containment areas, I used to climb 250 stairs a day. I only have a six-storey building so, I used to go up and down 42 times and I did Everest in about 16 days. And then I went up to a place where they opened the roads and I could go and walk and run through roads with the mask and glasses at the highs and lows of Bombay. Now I do a lot of work at the racecourse. I have been doing yoga as well.

What does your NGO do?

Child sexual abuse given the horrific statistics… It takes a lot time to heal, the game is prevention. So, we conduct workshops in schools and colleges, co-operative housing, we create modules for the teachers and parents, administration, canteens and staff to make them understand what CSA is and what they should be looking out for. So, creating awareness about CSA. We believe that development in the under-developed part of world only takes root permanently if the people of that region buy into that modular development. If development has to take seed permanently, it has to be tied to the people of that region.

What is the future of Rugby?

And when do we see Rahul as an author?I’d always like to become a writer that I would like to read, I don’t think I have reached there yet. I have been asked to write on many occasions, but I am not losing any sleep over it. Rugby, size matters. Technique is equally important. We have now begun to look to the big boys, new blood. Women’s Rugby is doing better than the men’s rugby. We are determined to look at Rugby and better it.