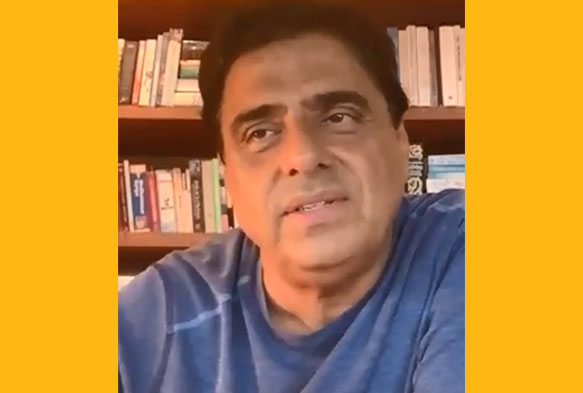

The last two-three months have been about understanding how to recalibrate.

Entrepreneur Ronnie Screwvala in conversation with Rtn. Dr. Prakriti Poddar

WHAT DO WE NEED TO DO TO BUILD THIS ECONOMY?

The last two-three months have been a situation of understanding how to recalibrate, now that one is forced to…. Part of the challenge is parental pressure to pursue degrees which lead to job opportunities, but we miss out on soft

skills. In India, soft skills are as important as hard skills. However, two-thirds of our population goes into the work force for socio-economic reasons without tanking up with the right kind of knowledge. Therefore, the only option for them is online. That is how UpGrad happened. The core idea is that all of us, including every single person here, will have to undertake formal learning and specialisation of some kind every three to four years.

However, there is no question that we have been struck with something uncertain. For the younger generation, reducing

uncertainty can bring about balance. It could be the steps that every organisation takes. For example, within months we told everyone, including social workers, in all our companies that we would be working from home till at least December 2020. That allowed people to acclimatize, go back to their families, let go of their PG accommodation or do whatever they needed to do. So, 20 per cent of certainty and balance comes into your life.

The second one is that performance is going to be important. We are not going to lay off people but we might not be able to do increments or we will do pay cuts so the certainty comes about and I think today, more than ever, leaders need to be candid, not inspirational or polite. The younger generation is looking at real and candid comments. They want to know that the person on the top knows what they are talking about, and is not telling me one thing today and something else after a month. Removing uncertainty, bringing balance, and enhancing trust is a step by step process. There is no such thing as over communicating at a time like this for colleagues or team members.

YOUR SWADES FOUNDATION SPENT RS 49 CRORE ON UPLIFTMENT AND ENRICHMENT PROGRAMMES ALONE, AND, IN THE LAST YEAR, YOU LOOKED AT THE INNOVATIONS SPACE AS WELL. HOW WAS THE JOURNEY?

The trust started in the late ’80s and 1990s. We did not have much then but we said that we would like to give back 10 per cent of what we do. So, from our 10,000 sq. ft. rented office space, we allocated 1000 sq. ft. to a creche and an old age home. It was a culture-making movement because the whole company adopted this 1,000 sq. ft. One could see that magic. I was very young, and I didn’t have resources. But sweat equity is as important as any other cheque.

In 2012, when we divested the company; Zarina was a little more heartbroken to move out from the media and entertainment business than I was. So, she went out to do a Teach For India 10-day course and when she came back, she said she was going to join Teach For India. I got a little worried at that stage. When I asked her why she didn’t do something within our organisation, she said I was not serious. In response I said to her ‘why don’t we lift a million people out of poverty in the coming six to seven years?’ This is one of the most expensive retention statements I have ever made. She looked at me and asked, are you serious about this? Serendipity is a strong word for me – sometimes, you walk into a situation and do things that are least planned. The mission statement literally got done because I wanted to retain Zarina and ensure she stays with us. That is how it started. We met so many incredible people across India. We met an organisation called BRAC in Bangladesh which had a holistic model.

In my opinion, it looked after 25 per cent of the GDP of Bangladesh because, as the number one dairy plant, it was for the people and by the people. It made us realise a couple of things:

a) We did not want to cut a cheque, we wanted to be fully involved. b) We were entrepreneurs and we wanted to build an organisation and do it in our own way. c) With my obsession of scale, whatever problem we wanted to solve – especially if it was in the non-profit space, did I want to do it at that scale?

I was obsessed that I needed an exit plan to go into geography and you should be able to exit it in 6 to 7 years. The first few months that I started using the word ‘exit’, everyone talked me down, saying that the word ‘exit’, in non-profit, would have people assume you were doing to abandon them some day. So, we changed the word to empowerment. But those were our four fundamentals.

Take the holistic geography of 2000 villages that we took in seven blocks of Raigad, all consecutive and fully related and solve the problem. Our key mission was that we would ensure water with two taps in each home. This decision took three months of deliberation because the community was upset about digging and the cost became 20 per cent extra more. But we convinced them that it would be much more liberating and would raise the self-esteem of the people there.

Next was to provide an attached individual toilet for each home. We do a lot in terms of thinking in terms of community toilets but we were clear that they wouldn’t use it if it is not an individual toilet.

In education, it came down to spending money on brick and mortar vs augmenting the teaching system. There are about 1200 schools and 800 anganwadis geographically and we installed libraries in 500 of them. Those were attendance-moving, needle-moving magical moments. It took some time because the principal had to accept that a period would have to be taken out for the purpose of the library.

Lastly, career counselling. I don’t think anybody in the rural area asks the kids there what they want to do.

My final, magical one, is that I feel all roads lead to livelihood. We look at the geography with a GDP approach; about 30 per cent of our people earn below Rs. 50000 per annual income for the whole household, about 40 per cent earns between Rs. 50,000 to Rs. 1,50,000 and some of the others are about that but less than Rs 2.5 lakh. We wanted to quadruple their income in the next five years – and that was our goal – to empower and exit. The reason for empowerment was that if they did not have money in their pocket, they would look for charity and they would not be in control. People in control of their destiny need an NGO, don’t need the government. That has been our approach. But 30-35 per cent of the households don’t have an earning member and they don’t have land. How do you solve a problem like that? We get into having a long-term income propensity. Therefore, communities need to be built. So, three years into our learning, village development committees came about.

One of the things that we did wrong in the beginning was to set our own targets because, as business people, we are used to setting our own targets. But when you are doing something for the community and when you are doing something in the not-for-profit space, you have to understand the targets they have set for themselves.

Today, just to sum up the livelihood part, whatever we invest, when Swades puts Rs 50 crore in to livelihood, the next year onwards there should be equivalent of another Rs 50 crore of augmented livelihood for those households on a recurring annual basis and that has been our benchmark. We can only do that and measure that with the GDP approach. Some of these have been really tough, incredible amounts of failures, a lot of resistance, but it has paid off.

TALKING OF MIGRANT WORKERS, CAN YOU HIGHLIGHT WHAT STRUCTURE AND SUPPORT SYSTEM YOU HAVE PUT IN PLACE?

For the past five years, we have been pushing for reverse migration and the reason is that even in our Raigad district and in most places, 30-35 per cent of households in the villages are locked because the people come here. For the last five years, we have met people in Mumbai from Raigad District and find out that 95 per cent of them are not that happy. But the main reason they would not go back to the village is because it would be like admitting defeat. Further, they live here on a monthly salary of Rs 10-12,000 but they cannot send back more than a thousand. And they live in abysmal surroundings here. Corona was a massive impetus for everyone to get the hell out of the city because they were not going to get their salaries for a couple of months.

The migrant population in India is ignored because they are neither urban nor rural and even politicians could not have anticipated the level of that migration instinct because they have forgotten about them. We have been working with them and we got about 150-160 people reversed back to Raigad in our blocks. That would have been a big moment for us but then we had 75,000 people from our geography that migrated back in three weeks. The villages were incredible in organising the quarantine process. At the end of that, we had only 17 Covid cases and four deaths. Then, the next surge that came in took numbers from 75000 to 1,98,000 and that gave us a lot of challenges.

All of us feel that if they come back, they might be in a better position because they will demand higher wages, whether in construction or real estate or F&B. 65-72 per cent want to come back when the jobs open up but a lot of them want to come back with 30-40 per cent hike in their salaries.