The Meaning Of Conservation

Conservation architect Vikas Dilawari warns that meaningful restoration is suffering from indifference

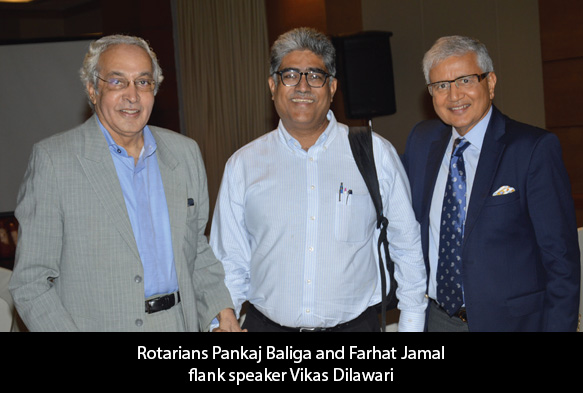

EXPERIENCE counts and so it was a delight to hear Conservation Architect Vikas Dilawari at the Club meeting last Tuesday. Vikas’s beautiful presentation packed fabulous images of before and after restoration works that kept the audience engrossed.

The conservation movement started with the World Wars and the Industrial Revolution, when the need for reviving arts and crafts was felt. Vikas defined conservation as an elephant left to the interpretation of blind men. “Historians don’t want change; developers want full change; society is unconcerned; for the government, development is on the agenda but conservation is never; ordinary FSIs are happy to break an old building and construct high rises and just a miniscule number of conservationists like me try to bridge the two extremes – architectural historians and builders.” “The reality is our cities are not maintained because of the Rent Control Act. So, we have low rents and frozen rents. Preservation is restricted to monuments, restoration is just emerging, and skilful repairs are missing,” Vikas pointed out. With decades of experience behind him, Vikas shared the basic fundamentals followed by conservationists:

- Minimum intervention

- Use of like to like material

- 6 inches – 6 yards concept

- Documentation of complete work

TODAY’S SPEAKER: ANANT GOENKA, MD, CEAT ON ‘WHERE THE RUBBER HITS THE ROAD’

Vikas said, “We always advise reversible intervention which is more difficult to follow” The most important fundamental is to avoid experimentation.

“There are many challenges in this field as we have been at it for just three decades. Whereas, Britain has done it for two centuries. Clients are not aware of the conservation aspect. There has been a disconnect and loss of tradition and skill as traditional materials are not easily available. Poor appreciation of work leads to poor remuneration for the craftsman.”

“Every project tries to revive craftsmanship. But we don’t get traditional materials, so new materials are being used. Is that conservation? If you see the recent example of CST station, the traditional glass was something else and what has been used now is something else. There is no historic study so we lose continuity.”

“Most of the conservation work in Mumbai is under the disguise of beautification. Beautification is quick, conspicuous, expensive and undesirable. The bureaucrat who commissions it is happy to see it complete in his tenure, but the building is unhappy. Conservation is slow, inconspicuous, economical and desirable. It will certainly not happen in the tenure of a bureaucrat.”

Next, Vikas moved to some alarming statistics. Mumbai was the first city to have a Heritage legislation and the first list (later revised). Mumbai has two heritage sites and one National Park unlike any other city. The heritage works up to only 7.5 per cent of the city but unfortunately with the new DCPR, 203-04 half of the grade 3 building do not need to come under heritage committee. So, 7.5 percent has been reduced to 3 percent and it is very miniscule.

Interestingly, when Mumbai developed during the 19th century, the new development of then became today’s World Heritage site while today’s development is certainly not going to be one in the future. “We do have problems,” said Vikas, “we have more than 16,000 properties that are over a hundred years old and the Rent Control Act does not allow them to be looked after.”

“The government does not want to address the Rent Control Act, but the other proposals are to invite private builders, leading to a redevelopment such as Bhendi Bazaar which is cited as a good example of cluster development.” Vikas feared the ability of Mumbai city to cope during any disaster. “This is the reason why conservation comes into the picture,” he said.

Vikas, through a PowerPoint presentation, gave a brief and chronological outline of his experience of restoring heritage private and public buildings/structures. Starting from the American Express Bank, Amarchand Mansion – residential building, Simone Departmental stores, restoration of the Army Navy building, Rajabai Tower restoration

of glass by using minimum intervention.

The Intach Mumbai Chapter approached him after the fire at BMC building hall in 2001, and had Vikas involving craftsmen to restore small details, arches, the gold guild and ceilings of the building damaged in the fire. Vikas also shared experiences while restoring the Aga Khan palace in Pune which was declared unsafe by the PWD. What was unsafe was a toilet portion, easily fixable. The team got the colour scheme back and made it functional again. The Bhau Daji Lad Museum, an excellent example of public-private partnership, was transformed too. There is a lot of trial and error and experimentation in the process, lots of referencing and with the right archival materials you can get back to the original, he said.

Not just public buildings, Vikas does private bungalows too. One at Matheran was restored by Vikas and team in 2008 with simple things in an economic way. Hira Baug, a simple building in Bhuleshwar is close to Vikas. While they were working on it, they found some stencil marks and they found HB written on it (which stood for Hira Baug). The Elphinstone building which caught fire was challenging for restoration as there was no open space, but yet was successfully done by replicating the roof exactly as it was.

Conservation is not just about Heritage buildings but also the rundown buildings. Vikas showed slides of a functional toilet, totally rundown but after two years of hard work, the restoration was beautifully completed. The residence of Jamshedji Tata, too, was restored. It took Rs 3 crore in 10 years to restore the building, the grand images were jaw-dropping.

Another building close to Vikas’ heart was a building at Meadow Street. The developer-owner approached Vikas to transform the building to be rented. The transformation was wonderful which stemmed the improvement of the surrounding buildings.

Talking of fountains, the Mulji Jetha Fountain which did not see any water spouting from it in the last 50 years has now been made functional and owners of nearby hotels are looking after the fountain. Willingdon Fountain too has been restored to its marble and brass materials. The Flora Fountain was restored hopefully now to be taken good care of by Municipal Corporation. Thus, big and small, private and public, glamorous and rundown, Vikas has restored all with minimum intervention and all with heart.

Finally Vikas concluded with four points,

- Can today’s architecture be tomorrow’s heritage?

- Conservation economics is an important in a developing nation like ours.

- Change is an inevitable part of nature. Change for need is permissible but not for greed. Need base change integrates well into development. It’s the latter that creates conflict.

- Least bad compromise rather than the best possible solution is a practical way forward.