WHERE DO YOU WANT TO GO?’

POLICYMAKERS AND LEADERS MUST ASK THE PEOPLE WHAT THEY WANT OF THEIR FUTURE. HUMAN KIND ITSELF, AS A SPECIES, MUST KNOW THE ANSWER TO THIS QUESTION

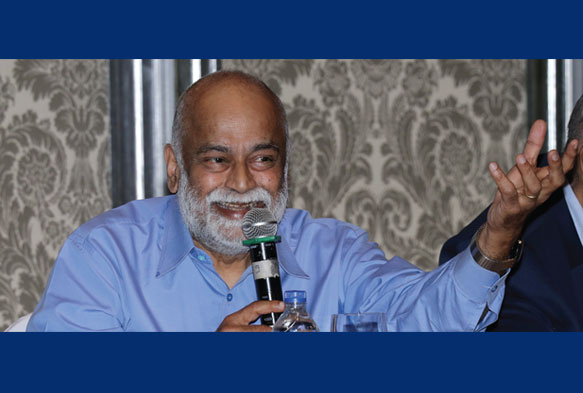

Indian-American anthropologist Arjun Appadurai has lived in the US for 50 years while his research and teaching has revolved around India. Many of the Rotary Club of Bombay’s Rotarians knew him and so Arjun was honoured and happy to address the Club last week.

The Future as Cultural Fact, the topic of his talk as well as the title of his book, takes a broad, analytical look at the genealogies of the present era of globalisation through essays on violence, commodification, nationalism, terror and materiality. India being at the heart of his work, Arjun offers first-hand research among urban slum dwellers in Mumbai, in which he examines their struggle to achieve equity, recognition and self-governance in conditions of extreme inequality. In his works on design, planning, finance and poverty, Arjun embraces the “politics of hope” and lays the foundations for a revitalised, and urgent anthropology of the future.

As an anthropologist, Arjun is not involved in the part of anthropology which is involved with evolution, history,

archaeology, monuments, stones, rock. He says, “That is archaeology, those are my colleagues. But, I work on living

societies, like our society here and other societies. So, I am in the social-cultural branch of anthropology which is not about the long-term human evolution. It is about here and now.”

Any society big or small, rural or urban, is always worried about the future. Be it worry about the weather, children

or agriculture. He says, “And yet 90 per cent of anthropology is about the past: people talk about memory, history, what they did, what their fathers did, what their grandfathers used to do. It leaves at least half of all human activity out of the field of attention, and that is the future. That is shocking.”

“Let us talk about Hindu culture,” adds Arjun. “What is the Hindu view of the future? Who knows! Why? But if you talk

to each other, you will find specific ideas about where you want to go, thoughts about tomorrow, about life, about the planet and these ideas may be partly religious in origin or professional, but we have to ask. So, my book is premised on what would happen to anthropology if we took a single idea seriously: that all societies have a picture of the future. The anthropological twist is because not all those pictures are identical. If I go to Indonesia, for example, and ask, what is your future? I may not get the same answer as elsewhere. It may not be about the next life, it might be about this life, it might not be about getting richer – it might be about getting poorer, getting rid of your possessions.”

It is such situations that add to the rationale for studying this question and its outcomes, says Arjun. “It affects policy. If one doesn’t know what people want, what kind of politics will one play? What kind of public policy will one create? What kind of debates will one have? It is important, not only for scholarly purposes, but also for purposes of planning, politics and public life because otherwise the future will always get smuggled in when you are talking about something else.” Arjun talked Rotarians through this with the metaphor of a a cultural car. The way anthropology operates it is by driving while looking only at the rear-view mirror. He asks, “But what about the big windshield in front from which we can see the road ahead; where do we want to go to? Do we want to turn or do we want to stop? That is absent because human beings are only looking at the rear-view mirror. So, we are missing a lot. It is not hard to fill that gap but it requires effort, training, discipline and reading.”

This led Arjun to bring up the importance of forecasting, prediction and speculation and, also, imagination. Thus, there is a mix and how that mix works is different from one society to another. Fear is also a factor that Arjun highlights as shaping people’s experience and imagination which always has to do with the future rather than the past.

Arjun then showed how studying the future from an anthropological perspective is productive in understanding contemporary finance as it affects all individuals irrespective of their economic backgrounds. Derivatives form a major part of this. Huge markets, where all are involved due to some or the other kind of debt, can cause very high level debt: corporate debt, national debt, car debt, housing debt, medical debt. “In the US,” says Arjun, “everybody is in 110 per cent debt for a hundred things. Any crucial good in their life be it education, health or housing, whether theirs or their parents, is based on high leverage; 10 per cent down payment, rest borrowed. Our debt as common people is the basis for financial markets. So that is where the derivative trend gets its material to trade; it is not through printing money – it is from ordinary debt but that is then leveraged up through derivative mechanisms into a huge global market which is many times the size of the GDP, or many times the size of the markets of real goods and services.”

What draws an anthropologist’s attention to this is their cultural approach to risk. How much risk can someone tolerate? Will it make a difference whether they are in a city or village? Will it will make a difference if they are Indian or Japanese? What is their risk level? What are they speculating? Why are they investing? Which things do they like to invest in? Which things do they not like to invest in? Why do they go in to debt at all? What is the promise about “later” which affects “the now”? After shooting off so many questions to ponder upon, Arjun concluded his comments by saying, “Studying the future from an anthropological point of view offers both a path to understand ourselves, but also to understand things which we think are totally technical subjects, like the derivative market. It seems like an unidentified flying object which nobody can understand but the truth is that it is related to how different groups in a society try to bring future values into the present and that makes it a subject of interest to people like me!”