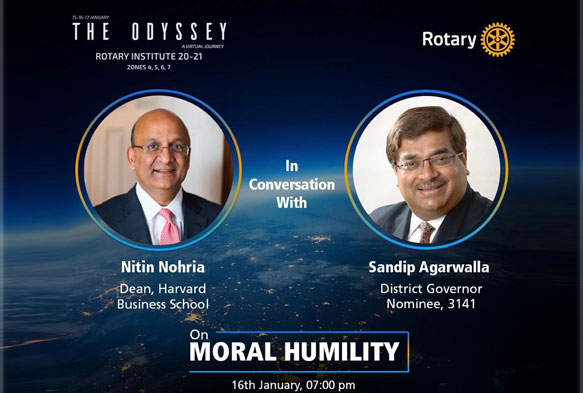

DGN Sandip Agarwalla (District 3141) Engages Nitin Nohria, Dean Of Harvard Business School In A Conversation On Moral Humility

DGN: Nitin Nohria is an Indian-American academic who serves as the 10th and current Dean of Harvard Business School (HBS) and the George F Baker Professor of Administration. He is also a former non-executive Director of Tata sons. During his tenure at the Harvard Business school, Nitin has made a lot of changes; he focused on business ethics and made HBS more experimental and, especially, more global.

DGN: He is one of today’s most sophisticated corporate thinkers, not only in management and strategy but also his intellectual interest centred on human motivation, leadership, corporate transformation and accountability and sustainable economic and human performance.

DGN: Rotary is a global network of 1.2 million neighbours, friends, leaders and problem solvers who see a world where people unite and take action to create a lasting change across the globe in our communities and in ourselves. Solving real problems takes real commitment and vison. For more than a hundred years, Rotary’s People of Action has used passion, energy and intelligence to take action on sustainable projects from Literacy to Water and Health, and we are always working to better our world and we stay committed to the end. In this quest, it is imperative to bring into its fold persons with a good moral compass which is why Rotary chooses its members, be engaged in the challenged sections of society. Rotary’s work is the chorus of hope around the world.

DGN: Watching societal discourse, one often experiences a longing for authentic discussions of the core values that should be guiding us, the tiers that are morally adrift. It is not that society is largely immoral, just amoral lacking the clear compass or foundational guide. Humility is that crest of excellence between arrogance and loneliness. Moral humility is a matter of balance. Neither do people with moral humility believe that they have low moral worth nor do they see themselves as moral authorities. They see their own moral competence accurately. Morally humble people also appreciate the moral strength and behaviours of others. Moreover, we focus on moral learning ability to learn from others for support and admit mistakes. Winners with these abilities generally bring about less unethical behaviour on the part of followers. We are fortunate to have, with us today, Dean Nitin Nohria and to have a conversation with him on moral humility.

NN: I am excited to be a part of this conversation; my father was a member of the Rotary Club in India and served as the Chair of one of its chapters. I have a warm and long affection for the Rotary Club.

DGN: I don’t know if you are aware but the Rotary International President Herbert Taylor introduced the Four Way Test in 1931 which is a test of the things we say or do and has been used by Rotarians worldwide since the last 88 years as a moral code for personal and business relationships. The test can be applied to almost any aspect of life: Is it the truth? Is it fair to all concerned? Will it build goodwill and better friendships? Will it be beneficial to all concerned? This is Rotary’s lodestar, how relevant do you think it is today?

NN: It is extraordinary when you hear the Four Way Test, if we were to apply it today, how much better the world could be. If you think about the first test, is it true? People are describing that we are living in post-truth world. The idea that what we say is true and we should be attached to the truth. Harvard’s model is a permanent search for truth. So, in some ways, there is such resonance to the core value that Rotary has in its first test.

NN: Is it fair? Covid has revealed to us that so much of society is unfair, the cost of most tragedy is borne by the most vulnerable far more than most of us who are privileged. You and I can escape in the comforts of our homes, socially distance ourselves and take care of ourselves. Even in the US and rich countries, there are people who have considered themselves as essential workers who are often the poorest workers, they are the ones who are still coming and for them to earn their livelihood means they are taking risk of Covid. So, we are learning in so many ways that if we ask ourselves is it fair, we would do a better job.

NN: Does it build goodwill? We live in a world where political opposition is turned into people not able to have dinner conversations with each other. We shudder to invite people with different political persuasions who are our dearest friends sometimes to dinner parties because we worry our friendship might be diminished by these divisions that we now experience. So, to build relationships in which our goal is to promote goodwill is such an important thing.

NN: And the fourth test which is, in the end, the most important, is it beneficial to all? We are actually in the business of improving society in the interest of improving the welfare of this planet and in some ways in that test what Rotarians remind us is that while we are each individual, we are also members of society. So, society as a whole suffers if, somewhere, we suffer too. It is of course important to be other-oriented but even if we think of enlightened self-interest, I think is good for us to always ask the question, is what we are doing beneficial for others? So, I think it is a fabulous Four Way Test and if more people follow that today, the world will be a better place.

DGN: I think the beauty of it is that it is timeless and the way you explained it, it is beautiful.

NN: It feels timeless but it is more poignant today. It sometimes has a special resonance at a moment in time, as I hear the 4-way test, it feels to me more relevant today than it was.

DGN: When we see examples of ethical and moral failure, our immediate reaction is to say that this was a bad person; we like to sort out the world into good people who have stable and enduringly strong positive characters and bad people who have weak or frail characters. So, why do seemingly good people behave badly?

NN: This is one of the great moral questions that people have asked. I came to think about this question very deeply through the work of a great social psychologist and moral philosopher by the name Stanley Milgram, a Jewish professor at Yale. In the aftermath of World War II, he couldn’t understand how the entire nation of Germany could have done what they did to Jewish during Holocaust. He says is it possible that everyone of these people was evil? To believe that you have to lose your humanity, right? To believe that there is a group of people where everyone is personally evil. So, he conducted certain experiments at Yale where he invited a group of people off the street, a randomly selected group of people and they were put in a setting where they were the instructor and there was someone else who was the learner and if the learner made a mistake, they were supposed to give an electric shock to the learner to try and encourage them to do better the next time. And, of course, what they did not know was that the learner was the confederate of the experimenter and not a real learner. They thought it was just another person because they’d invite two people in the room and they would draw a card and one person would be put in learner configuration and other in teacher. What they did not know was that the learner was always the experimenter’s confederate. The learner was taken into a room and had electrodes attached to his arms, and the teacher and researcher went into a room next door that contained an electric shock generator and a row of switches marked from 15 volts (Slight Shock) to 450 volts (Danger: Severe Shock).

The learner purposely gave wrong answers (on purpose), and for each of these, the teacher gave him an electric shock. When the teacher refused to administer a shock, the experimenter was to give a series of orders/prods to ensure they continued.

Two-thirds of the people were willing to give the learner an electric shock up to the level of severe shock just because there was a person in an authority position who stood there as an experimenter telling them they were required to do so for the experiment to continue. If the person said, I am feeling uncomfortable, all that the person would say is that the experiment requires you to continue. It’s not that if they stopped and refused to administer the shock, they would be put in handcuffs or be imprisoned or be penalised. It puzzled Stanley Milgram and, me too, that two-thirds people like you and I could have been the people ended up giving electric shocks to innocent persons just because someone in the authority said that that was something that we needed to do. So, that was the root of recognising that we all have moral over-confidence. So, when we show those experiments to our students at Harvard, we ask people to write privately whether they thought that they’d be in the 2/3rds —how many do you think admit? Less than 10 per cent. So, we all somehow feel that I’d be that morally brave person who would have been able to stand up in that situation, and it is all these morally weak people who end up doing the bad things. It is important to realise that there are many societal influences that might cause us to behave in certain way. It can be a time or person in authority, we can justify the things as per societal norms; bribery is the way in many parts of world. We can justify the do’s by saying everybody else does it. It can be under the pressure of incentives. We saw this at Wells Fargo that the company creates incentives for what people do, get bonuses based on how many accounts they open and it is little surprise that that many people have to open the accounts. So, it can be done under time pressure, people might feel that I don’t have time to get this done so, I am going to cut corners. So, there are many societal influences learned overtime that could cause us to stray from our core moral values. That doesn’t mean we don’t hold those values, there are times, when under pressure, we may betray the values we hold dear and at other times we may follow them.

DGN: With leadership and intellectual over-confidence comes power; how does one disabuse this person so that he doesn’t suffer from moral over-confidence?

NN: When Abraham Lincoln led the US through the Civil War, he was once asked: how do you test a person’s character and people say adversity shows us the true character of a person. Lincoln said: Having lived through a period of great adversity I think that people rise to adversity and show the better side of their character in adversity. The real test of a person’s character is to give them power. He said he had seen so many people – soldiers promoted to Sergeant or General – something about the power gets into their head and their character and power being more challenged and morality being suspected. So, as a person who has taught leadership and is a part of an institution that is going to produce people who are likely to gain more positions of power in time, I have been thinking this a lot: what can we do to enable people who become more powerful and sustain their moral humility. The only answer I could come up is, the Indian answer of who you surround yourself with – the idea of sangat is a very powerful idea. It is not about who you surround yourself with but do you create a condition where they can call you on the mistakes that you make? Do you remain open to the people who are around you, who are saying to you, I am not sure that it is consistent with our values, or you are not consistent with your own values. Having these truth speakers around you because whenever you are in a situation like this, there is a person who spoke up and said this is wrong, the question is, was that person listened to? Was he paid enough attention to? So, we cannot, in these moments, easily believe that there can be something in us – we have to rely on team work. This is where having people in the team whom you trust and when they call you out you will listen to them, that is the only systemic defence I have seen of people who remain morally humble over a period of time.

DGN: The recent crisis has shown a number of fragilities in many areas. Geopolitical tensions, economic inequalities, revelations of working from home have affected many sectors badly. Jobs, real estate, migration sector in India, do you think values and ethics have taken a hit both in business and government?

NN: Some of the failures in our values have been exposed very deeply. Maybe I am an eternal optimist, but these can be opportunities for recovery as well. So, just take what was perhaps uniquely American but in some way reflects issues that exist everywhere in the world, which was the racial issues that came to the forefront in the middle of Covid. We were already learning that the people affected in Covid were disproportionately from under-represented minority communities in the US. Then we had the killing of George Floyd that led to America having to come to terms with its racial inequalities. It was a very painful moment to confront this moral failure that how is it the case that again and again and again you find yourself in a place where innocent Black men and women are being killed. It is horrifying. There was a great book written on Caste by Isabel Wilkerson that shows that those of us from India should be extremely mindful because we have a similar system in India and if you go all over the world you will find that there is a caste system of some kind. So, I hope that this moment would reveal how over time we almost learnt to neglect these inequities in society or almost live with them. I thought hard about how we experience poverty every day in India but we have become numb to it. That is the state of the country. I hope that this is the moment in which the short way in which our moral shortcomings have been revealed will actually lead to a moral awakening. I certainly see that in race in America, I see a moral re-awakening and that gives me a little bit of hope, as they say the darkest hour is the hour before the sunrise and maybe I am permanently optimistic in that way but I do feel that this is a time that will hopefully cause us all to think. How do we make sure that this is not the world in which we are going to live going forward?

FOR THE COMPLETE INTERVIEW, SEE THE GATEWAY ONLINE:

http://rotaryclubofbombay.org/category/past-issue-archives/